This is another one of those occasions, after a looooong break, where this blog gets dusted off to put up a version of a talk. This time it’s for SPANZA 2024 (that’s the paediatric anaesthesia conference for Oz and NZ being held in Melbourne). It’s a combined conference with the ENT surgeons and the topic of the day is ‘Extubation Timing’.

This post is about the end of it all. And about time.

Go to most conferences and there will be talk after talk on putting breathing tubes in patients (ensnorkelling them I guess). Hit the FOAMed land of the interweb and you’ll find passionate beliefs set in concrete relating to hyper-niche difficult airway scenarios that only exist in hypotheticals or overwritten medical soaps. At some point in this meeting people will head off to a CICO workshop to prepare for a paediatric airway scenario that is as rare as hens’ teeth. Actually as rare as finding a tooth on a hen and that tooth also being on a hen that can tell you that incisor is called ‘Chopper’.

Wow. A talking chicken.

But pretty much every time we place a breathing tube we have to take it out.

So it’s about time.

Of course the job here is to seize this opportunity and lay out in exquisite detail all the wonder and nuance of the evidence that exists around timing of extubation. It’s my job to present all of the forest and all of the trees when it comes to extubation.

There’s just one problem with that – it’s a pretty foggy landscape.

The combination of very little actual evidence in the area, even to the point of lacking a shared understanding of what we mean, leaves us a bit stuck. This might be because extubation is a bit fuzzy. It doesn’t come with the same cool gear as airway management at the start of a case. It doesn’t come with things that are relatively easy to measure like ‘time to intubation’ or ‘first pass success’.

We’re at risk of just ending up chatting about ‘things we reckon’ based on stories we were told by this one old anaesthetist in the tearoom. But even with a pretty sparse evidence-base to work with we can make a serious effort at coming up with a way to think about wrangling the very imperfect moment of extubation.

Not Very Imaginative Imagining

Let’s imagine something that feels pretty commonplace.

It’s a Friday. It’s the emergency list. A booking gets dropped in some time after the morning ward rounds for an extubation in the operating theatre. The patient is 6 years old and they have had a revision of their laryngotracheal reconstruction a few days earlier, all happening on a background of a recurrent bronchitis picture and slightly abnormal airways. The surgeon is available after 15:00.

Now naturally enough this is not an actual patient. It is a heap of patients mashed inelegantly together. But it could absolutely be a real patient.

It is definitely the sort of patient that got us thinking locally that maybe we needed to put a bit more thought into the end of the flight. For all the lazy use of flight as something ‘a bit like anaesthesia’, it is fair to note that the end of a flight follows a planned and well briefed sequence, not a bunch of vibes you picked up along the way.

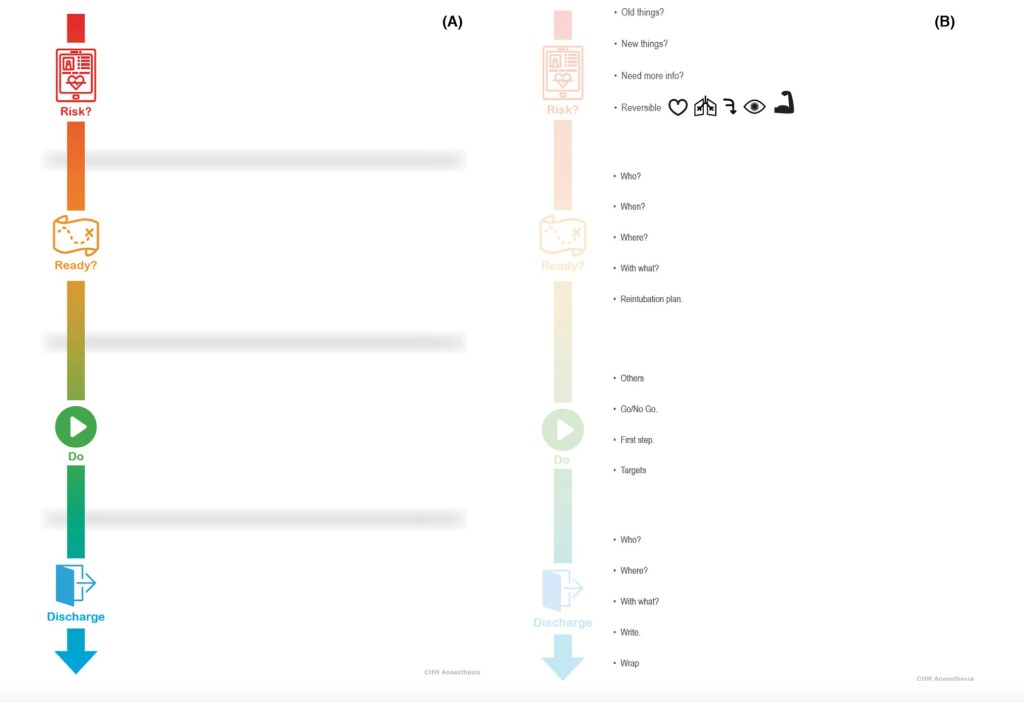

We’re by no means on our lonesome when it comes to wanting a bit of a plan. The Difficult Airway Society has some. The Canadians have also come up with something. Which is why we came up with a pretty straightforward planner to work through. 4 simple steps:

- Risk

- Ready

- Do

- Discharge

Or R2D2.

I guess we just wanted something unique. Something no one had ever heard before. Something with no cultural reference points and free of all risk of trademark disputes.

And it looks like this:

The fundamental principle, a little like the Airway Decision and Planning Tool for kicking off with a difficult airway, is to get the team on the same page. This starts with a background understanding of what we might figure is a ‘difficult extubation’.

We went with this definition:

A difficult extubation should be anticipated when the airway clinician assesses that it is likely that additional techniques, oxygenation methods, or ventilatory support will be required to support the patient after extubation, or when reintubation is likely to be difficult.

The phases of R2D2 should kind of explain themselves:

Risk

Getting a sense of the risks is pretty fundamental to making a plan. In fact the DAS version has ‘Plan’ up front but in fact they’re really talking about risk for a lot of it. So it felt like it made more sense to label it ‘Risk’.

‘Risk’ is about both assessment and optimisation. It emphasises understanding the patient, capturing the clinical picture and making sure everything possible has been optimised to guarantee success.

Kick off with all the things that always exist for this patient – are they known to be difficult when it comes to face-mask ventilation (they need heaps of CPAP, always need adjuncts or two-person techniques … whatever makes you sweat). Are they known to be difficult to intubate? Have they failed extubation in the past? Do they have a background of always needing non-invasive ventilation or neuromuscular weakness?

Then, out with the old (kind of) and in with the new. On this admission have novel things popped up that might suggest this extubation will be difficult?

It doesn’t really matter if it is new airway trauma or oedema, acute respiratory pathology or muscle weakness or that you have just figured out intubation is challenging in this patient. New stuff counts.

Anything messing about with access to the airway also matters. Looking after someone with a halo in place or some form of cervical traction is a guarantee of a harder day at work when it comes to extubation.

Could you use more information? A decent proportion of extubation failure in the intensive care setting relates to upper airway obstruction. In which case direct laryngoscopy or nasendoscopy prior might give clues as to the current state of play. Perhaps imaging will add bonus points of understanding. It’s a less frequent issue but sometimes investigations will add a little.

And then the big one – reversibility.

This is just the flip side of ‘is the patient as ready as they can be?’

Which means optimised cardiac and respiratory status.

You are hopefully sure that every bit of reversible airway pathology has been reversed, which might also include administration of steroids given there is a bit of evidence for that. A systematic review by Kimura et al in 2020 suggesting that those given steroids had lower odds of having post-extubation stridor or extubation failure (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.2-1.4) though dosing regimes show a significant degree of variance. Timing might count with one of the individual trials around when we were putting together R2D2 suggesting better results when dosing was for 24 hours prior to extubation rather than 6 hours.

And of course it’d be ideal for the patient to be at the right state of wakefulness (yes, that explains the slightly freaky eye graphic in that picture) and with as much muscle strength as they can muster. Reverse and reset everything you can.

And then get busy getting ready.

Ready

This is the bit where you get everything ready for success.

‘Who?’ is pretty obvious. You want experienced people in the room. That possibly also means your friendly ENT crew. ‘When?’ is all about timing for both the highest rates of success and the best support around if the patient has a slightly later failure of extubation over a few hours.

Ideally ‘when’ means in the morning. That way if there is a later need for re-intervention, it’s pretty likely everything will happen when lots of experienced people are around.

‘Where?’ – well for our difficult patients that will mean ‘in theatres’ most of the time’.

‘With what?’ is a simple reminder that you should start getting ready whatever option you’ll need to support their breathing and ventilation after. There is some evidence supporting non-invasive ventilation and some showing high flow nasal cannula oxygen does the job. Whatever the choice, you need step 1 in respiratory support ready to go.

And of course you need a reintubation plan. Sometimes that’s just the sort of day it is.

Do

Planning and getting ready is great. Doing is better.

It’d be easy to describe this as ‘just do the thing you got ready for’. Just do it.

But the prompts are a reminder that when it comes time to actually get things done, it is critical to pause for a team brief.

This should cover the ‘Other’ things you’re going to do with the extubation (something like an airway endoscopy, for example). The briefing should include a good chat about the ‘Go/No Go’ points – these are the elements defined by the team so everyone knows what they can look for to confirm the extubation should proceed. Of course the ‘No Go’ items are signs that today is not the day.

They might be things you see at airway endoscopy. They might be about physiology – saturations or CO2. They might be ‘go/no go’ items defined by clinical assessment of work of breathing or degree of obstruction.

The brief should include coverage of what your first step will be to support the airway.

And of course the brief should include the targets everyone agrees are an indicator that the whole adventure looks like a success.

Discharge

But short-term victory isn’t the end of the story. Our patients probably want to stay in a good place so discharge planning is highly relevant to a comprehensive strategy.

That means it is really vital to know who will be looking after the patient and have a direct chat. Including anyone who might be snared by things later if there is a subsequent deterioration. It might not be you dealing with a reintubation it might be your colleague and they’ll appreciate a heads up.

Where will the patient go to? ‘With what’ will you support their breathing.

Finally make sure the details of the extubation itself and the plan for ongoing care are clearly documented and that every other part of their care is wrapped up – any ongoing steroids, analgesia and sedation considerations… the basics of good patient care.

Hopefully it is clear enough that there is value to having a bit of a strategy carefully considered and fully shared with the whole team in the room. For our 6 year old maybe it’s the difference between a slightly underdone end-of-day extubation plan and a trip where every last thing is optimised, extubation occurs at the start of the day and the right support and ongoing care is available immediately to make sure that all work of breathing is minimised and they can really fly after their case.

Ultimately the goal of all of this is to make sure that we take the extubation part of a challenging airway just as seriously as the intubation part. After all, this is the bit that hopefully gets the patient back to the rest of their life.

All Day, Every Day

Of course, the more common bit of extubation planning is *literally every other case*. Whenever we put an airway device in, we generally have to take it out. So getting handed the topic of ‘extubation timing’ kind of opens up the option of chatting about something that sometimes draws out surprisingly strong opinions.

Awake vs Deep Extubation

Again, there’s not a heap of evidence to work with here. And to be honest it’s tempting to take up the freedom to go with ‘just do this because I reckon’. Stating very strong opinions based on not much more than personal opinion and the thoughts of your buddy has actually worked for a lot of illustrious medical types over the years.

But perhaps we can do slightly better than that and possibly reassure people that what they’ve come up with is pretty on the money.

The reality is that if you asked a heap of anaesthetists if they extubate awake or deep, they’d probably say ‘it depends… I do what seems right for that particular patient’. However, for the purposes of a talk or blog post reality is boring so let’s pretend that actually people are really intense and committed to *only one way*. If fake outrage works for the media let’s borrow that tactic for a few minutes.

Proponents of awake extubation would probably say that it guarantees protection from aspiration and airway obstruction. These are both bad things and, although not very common the consequences can be dire. Plus patients undergoing deep extubation obstruct more they’d say and that is also no good.

Those who love deep extubation would probably say that it avoids the coughing and bucking of the waking patient which can even be enough to increase the risk of postoperative bleeding, wound dehiscence (yep, that’s quoted in one of the papers) and desaturation. Plus to be honest it sometimes seems messier.

They also might note that it means you can get on with the next case which offers some benefits for that next patient who gets their surgery that little bit quicker.

But talk is cheap, what does the evidence say?

Sifting Through the Science

Not much actually.

The evidence is generally from small studies, just as often with supraglottic airways as endotracheal tubes, and often old enough that techniques are profoundly different. Halothane might not be the most relevant anaesthetic agent for a lot of practitioners.

Even in those studies looking at ‘deep’ extubation there is sometimes imprecision of what is considered a ‘deep’ extubation.

In a relatively recent meta-analysis out there the total number of available studies to look at was 17 which led to consideration of a total number of patients of 1881 patients. Just 11 of those papers looked specifically at overall airway complications. These are ultimately not huge numbers. When you drill down to just endotracheal tube studies looking at airway complications, the total included subject count is 319 patients. Yikes.

Nevertheless this review by Koo et al suggested that overall airway complication rates for all airway devices (including coughing, desaturation, laryngospasm and breath-holding) were lower in the deep extubation group (OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.33-0.96). However when you just looked at the endotracheal tube group the demonstrated suggestion of lower complications didn’t reach significance (OR 0.62; 95% CI 0.31-1.24).

On the flip side airway obstruction was more likely (OR 3.38, 95% CI 1.69-6.73). Though ultimately ‘airway obstruction’ here means a scenario that is not particularly hard to deal with if you are familiar with a jaw thrust manoeuvre. That association was still there for the endotracheal tube group (OR 2.67; 95% CI 1.03-6.94).

Noting that this is for a mixed anaesthesia/ENT surgeon audience it feels worthwhile specifically mentioning adenotonsillectomy. Again the evidence base is not massive, but a prospective observational study from Texas Children’s that probably reflects relatively modern practice and that was able to include a total of 880 children did not show any significant difference between any airway complications with awake vs deep extubation (with a rate of 18.5% in the awake group vs 18.9% in the deep group). The things that actually made a difference to complication rates were having an URTI within the prior 2 weeks, receiving the equivalent of 0.1 mg/kg IV morphine (or more) and a weight of 14 kg or less.

Of course none of the studies in this area look at long-term outcomes. It’s all just about the experience at the end of the procedure and in PACU.

Which all means we can return to reality because there is not a lot to get worked up about here. Both techniques work very well and have their place. This doesn’t mean we should be not thinking about how to minimise complications of course. A study by Vitale et al derived from the Wake Up Safe database highlighted 66 cases of airway complications associated with deep extubation (where the reviewers were really confident it was deep extubation) and 19 of those patients had respiratory events leading to cardiac arrest (15 of which were deemed to be preventable).

Of course, that database doesn’t offer up a denominator so I don’t mention it because I’m describing a horrifyingly frequent outcome. Just noting that it is real.

So all we can really do is use clinical judgment to apply a technique we’re good at well, having set ourselves up for success by optimising the good bits of that technique and anticipating and preventing those problems that might pop up.

That Wake Up Safe paper does highlight that when considering deep or awake extubation, there are still some patient groups where the risk profile suggests maybe going with awake. That is suggested as particularly the case for those with a risk of aspiration and those with a difficult airway.

So risk assessment is part of planning for the every day.

Each technique comes with particular practice points and a slightly different set of slight risks to get ready for. It is simple enough to make sure that you get any adjuncts that might be helpful for dealing with airway obstruction (possibly more relevant for the deep extubation group as an awake patient is unlikely to be keen on an oropharyngeal airway).

A way to provide CPAP addresses not just airway obstruction, but also laryngospasm if that beast darkens your door.

And pharmacology is your friend. Whether to ensure that the patient is deep (or to have handy to deal with laryngospasm as is the case with something like propofol), or to add agents that hit the sweet spot of ‘awake but tolerating the tube pretty well so coughing is less of an issue’, consider which drugs will be relevant to the chosen strategy.

And suction of course. Suction is definitely part of the routine.

When it comes to doing it there are a few bonus considerations that might help. Where there are definite clinical signs to predict successful extubation, use them. Happily for volatile anaesthesia, Templeton et al. actually did a very solid job of giving us the tools. So look for grimace, purposeful movement, eye opening, conjugate gaze and a tidal volume of more than 5 mL/kg. It’ll help.

In the deep extubation setting positioning probably has some value. There is a small amount of evidence from this paper that oxygen saturations in the first handful of minutes is better maintained in the lateral position. This is maybe partly explained by the fact that in the lateral position the area in the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal areas is slightly larger, suggesting that obstruction is less of an issue. At least as covered in this paper.

Another point to consider is the last move factor. Whichever technique you choose, it seems sensible to make the extubation the last bit. That is as an alternative to extubating then moving the patient to a different bed. The latter version comes with the risk of creating obstruction for the ‘deep’ patient. And for those patients where you’d aimed for ‘awake’ but maybe they weren’t quite there, it might be the movement that triggers major reflex activity.

And as a final point it should be clear enough that deep is deep and awake is awake. Which seems glib but if you’re truly aiming for deep extubation it seems important to make sure that the patient is truly in that state of breathing consistently but deep enough that you’d instrument the airway if it was the start. And the patient in the awake group should truly be in the awake group. Although in that group there is at least that constellation of clinical signs to rely on.

Whichever you choose you’ll still be relying on a couple of key points relating to the spot you discharge the patient to – the people in PACU and the facilities in PACU.

Which means that at the end of considering the timing for the every day case we looked at the risk profile, got things ready, got on to do the thing and factored in their discharge pathway.

Or used R2D2 all over that.

Which is not really that surprising because I wrote this thing so of course I brought it back to R2D2. But also it turns out that a structure designed for the difficult situation will often capture the mundane. It’s just that for routine operations we can utilise our cognitive shortcuts to get there without formally using different tools.

It Is Messy

The way this talk was framed suggested that there is some perfect moment where we can get everything to line up with perfection.

This is absolutely not how things work out.

What we can do is set up a structure that makes things slightly less messy at the time we think we’re in the ballpark of being ready to extubate. And that makes sure we’re ready to respond to whatever happens.

Because it’s not about getting timing right.

It’s about being ready for the time when it happens to you anyway.

Resources, Links and Miscellany

OK. Here they are all together.

The DAS Extubation guidelines are these ones:

The Canadian Airway Focus Group paper is here:

Our planner paper is here and open access:

The Kimura et al review of corticosteroids can be found here:

The other steroid paper mentioned is in Pediatric Pulmonology:

Moving onto awake and deep extubation. This is that systematic review, challenged as it is to find numbers:

The Texas Children’s adenotonsillectomy paper is here:

The Wake Up Safe database paper is right here:

Vitale L, et al. Complications associated with removal of airway devices under deep anesthesia in children: an analysis of the Wake Up Safe database. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022 Jul 15;22:223. doi: 10.1186/s12871-022-01767-6

That really excellent paper on extubation criteria after volatile anaesthesia is free to read (actually most of the links seem to be):

The lateral vs supine paper is here (not free to read unfortunately so this is the PubMed link):

Wow did you get all the way down here?

Maybe this warrants taking a few minutes to relax? But also you could watch this video while you do that and reflect on whether you ever managed this with your marbles when you were a kid.